- Home

- Stephen Kotkin

Stalin, Volume 1

Stalin, Volume 1 Read online

ALSO BY STEPHEN KOTKIN

Armageddon Averted: The Soviet Collapse, 1970‒2000

Magnetic Mountain: Stalinism as a Civilization

Steeltown, USSR: Soviet Society in the Gorbachev Era

Uncivil Society: 1989 and the Implosion of the Communist Establishment

PENGUIN PRESS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA • Canada • UK • Ireland • Australia New Zealand • India • South Africa • China

penguin.com

A Penguin Random House Company

First published by Penguin Press, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, 2014

Copyright © 2014 by Stephen Kotkin

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Photograph credits appear here.

eBook ISBN: 978-0-698-17010-0

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers, Internet addresses, and other contact information at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors, or for changes that occur after publication. Further, publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party Web sites or their content.

Version_1

for John Birkelund

businessman, benefactor, fellow historian

Those that understood him smiled at one another and shook their heads. But, for mine own part, it was Greek to me.

Shakespeare, Julius Caesar (1599)

CONTENTS

ALSO BY STEPHEN KOTKIN

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

DEDICATION

EPIGRAPH

PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

MAPS

PART I

DOUBLE-HEADED EAGLE

CHAPTER 1 | An Imperial Son

CHAPTER 2 | Lado’s Disciple

CHAPTER 3 | Tsarism’s Most Dangerous Enemy

CHAPTER 4 | Constitutional Autocracy

PART II

DURNOVÓ’S REVOLUTIONARY WAR

CHAPTER 5 | Stupidity or Treason?

CHAPTER 6 | Kalmyk Savior

CHAPTER 7 | 1918: Dada and Lenin

CHAPTER 8 | Class War and a Party-State

CHAPTER 9 | Voyages of Discovery

PART III

COLLISION

CHAPTER 10 | Dictator

CHAPTER 11 | “Remove Stalin”

CHAPTER 12 | Faithful Pupil

CHAPTER 13 | Triumphant Debacle

CHAPTER 14 | A Trip to Siberia

CODA

IF STALIN HAD DIED

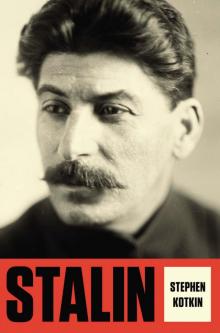

PHOTOGRAPHS

NOTES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ILLUSTRATION CREDITS

INDEX

PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Stalin, in three volumes, tells the story of Russia’s power in the world and Stalin’s power in Russia, recast as the Soviet Union. In some ways the book builds toward a history of the world from Stalin’s office (at least that is what it has felt like to write it). Previously, I authored a case study of the Stalin epoch from a street-level perspective, in the form of a total history of a single industrial town. The office perspective, inevitably, is less granular in examination of the wider society—the little tactics of the habitat—but the regime, too, constituted a kind of society. Moreover, my earlier book was concerned with power, where it comes from and in what ways and with what consequences it is exercised, and so is this one. The story emanates from Stalin’s office but not from his point of view. As we observe him seeking to wield the levers of power across Eurasia and beyond, we need to keep in mind that others before him had grasped the Russian wheel of state, and that the Soviet Union was located in the same difficult geography and buffeted by the same great-power neighbors as imperial Russia, although geopolitically, the USSR was even more challenged because some former tsarist territories broke off into hostile independent states. At the same time, the Soviet state had a more modern and ideologically infused authoritarian institutional makeup than its tsarist predecessor, and it had a leader in Stalin who stands out in his uncanny fusion of zealous Marxist convictions and great-power sensibilities, of sociopathic tendencies and exceptional diligence and resolve. Establishing the timing and causes of the emergence of that personage, discernible by 1928, constitutes one task. Another entails addressing the role of a single individual, even Stalin, in the gigantic sweep of history.

Whereas studies of grand strategy tend to privilege large-scale structures and sometimes fail to take sufficient account of contingency or events, biographies tend to privilege individual will and sometimes fail to account for the larger forces at play. Of course, a marriage of biography and history can enhance both. This book aims to show in detail how individuals, great and small, are both enabled and constrained by the relative standing of their state vis-à-vis others, the nature of domestic institutions, the grip of ideas, the historical conjuncture (war or peace; depression or boom), and the actions or inactions of others. Even dictators like Stalin face a circumscribed menu of options. Accident in history is rife; unintended consequences and perverse outcomes are the rule. Reordered historical landscapes are mostly not initiated by those who manage to master them, briefly or enduringly, but the figures who rise to the fore do so precisely because of an aptitude for seizing opportunities. Field Marshal Count Helmuth von Moltke the Elder (1800‒91), chief of the Prussian and then German general staff for thirty-one years, rightly conceived of strategy as a “system of expedients” or improvisation, that is, an ability to turn unexpected developments created by others or by happenstance to one’s advantage. We shall observe Stalin extracting more from situations, time and again, than they seemed to promise, demonstrating cunning and resourcefulness. But Stalin’s rule also reveals how, on extremely rare occasions, a single individual’s decisions can radically transform an entire country’s political and socioeconomic structures, with global repercussions.

This is a work of both synthesis and original research over many years in many historical archives and libraries in Russia as well as the most important related repositories in the United States. Research in Russia is richly rewarding, but it can also be Gogol-esque: some archives are entirely “closed” to researchers yet materials from them circulate all the same; access is suddenly denied for materials that the same researcher previously consulted or that can be read in scanned files that researchers share. Often it is more efficient to work on archival materials outside the archives. This book is also based upon exhaustive study of scans as well as microfilms of archival material and published primary source documents, which for the Stalin era have proliferated almost beyond a single individual’s capacity to work through them. Finally, the book draws upon an immense international scholarly literature. It is hard to imagine what Part I of this volume would look like without its reliance on the scrupulous work of Aleksandr Ostrovskii concerning the young Stalin, for example, or Part III without Valentin Sakharov’s trenchant challenge to the conventional wisdom on Vladimir Lenin’s so-called Testament. It was Francesco Benvenuti who presciently demonstrated the political weakness of T

rotsky already during the Russian civil war, findings that I amplify in chapter 8; it was Jeremy Smith who finally untangled the knot of the Georgian affair in the early 1920s involving Stalin and Lenin, which readers will find integrated with my own discoveries in chapter 11. Myriad other scholars deserve to be singled out; they are, like those above, recognized in the endnotes. (Most of the scholars I cite base their arguments on archival or other primary source documents, and often I have consulted the original documents myself, either before or after reading their works.) As for our protagonist, he offers little help in getting to the bottom of his character and decision making.

Stalin originated with my literary agent, Andrew Wylie, whose vision is justly legendary. My editor at Penguin Press, Scott Moyers, painstakingly went through the entire manuscript with a brilliantly deft touch, and taught me a great deal about books. Simon Winder, my editor in the UK, posed penetrating questions and made splendid suggestions. Colleagues—too numerous to thank by name—generously offered incisive criticisms, which vastly improved the text. My research and writing have been buoyed by an array of remarkable institutions as well, from Princeton University, where I have been privileged to teach since 1989 and been granted countless sabbaticals, to the New York Public Library, whose treasures I have been mining for multiple decades and where I benefited extraordinarily from a year at its Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers under Jean Strouse. I have been the very fortunate recipient of foundation grants, including those from the American Council of Learned Societies, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation. Perhaps the place from which I have drawn the greatest support has been the Hoover Institution, at Stanford University, where I started out as a visiting graduate student from the University of California at Berkeley, eventually becoming a visiting faculty participant in Paul Gregory’s annual Soviet archives workshop, a National Fellow, and now an affiliated Research Fellow. Hoover’s comprehensive archives and rare-book library, now skillfully directed by Eric Wakin, remain unmatched anywhere outside Moscow for study of the Russian-Soviet twentieth century.

PART 1

DOUBLE-HEADED EAGLE

In all his stature he towers over Europe and Asia, over the past and the future. This is the most famous and at the same time the most unknown person in the world.

Henri Barbusse, Stalin (1935)

RUSSIA’S DOUBLE-HEADED EAGLE NESTED across a greater expanse than that of any other state, before or since. The realm came to encompass not just the palaces of St. Petersburg and the golden domes of Moscow, but Polish and Yiddish-speaking Wilno and Warsaw, the German-founded Baltic ports of Riga and Reval, the Persian and Turkic-language oases of Bukhara and Samarkand (site of Tamerlane’s tomb), and the Ainu people of Sakhalin Island near the Pacific Ocean. “Russia” encompassed the cataracts and Cossack settlements of wildly fertile Ukraine and the swamps and trappers of Siberia. It acquired borders on the Arctic and Danube, the Mongolian plateau, and Germany. The Caucasus barrier, too, was breached and folded in, bringing Russia onto the Black and Caspian seas, and giving it borders with Iran and the Ottoman empire. Imperial Russia came to resemble a religious kaleidoscope with a plenitude of Orthodox churches, mosques, synagogues, Old Believer prayer houses, Catholic cathedrals, Armenian Apostolic churches, Buddhist temples, and shaman totems. The empire’s vast territory served as a merchant’s paradise, epitomized by the slave markets on the steppes and, later, the crossroad fairs in the Volga valley. Whereas the Ottoman empire stretched over parts of three continents (Europe, Asia, and Africa), some observers in the early twentieth century imagined that the two-continent Russian imperium was neither Europe nor Asia but a third entity unto itself: Eurasia. Be that as it may, what the Venetian ambassador to the Sublime Porte (Agosto Nani) had once said of the Ottoman realm—“more a world than a state”—applied no less to Russia. Upon that world, Stalin’s rule would visit immense upheaval, hope, and grief.

Stalin’s origins, in the Caucasus market and artisan town of Gori, were exceedingly modest—his father was a cobbler, his mother, a washerwoman and seamstress—but in 1894 he entered an Eastern Orthodox theological seminary in Tiflis, the grandest city of the Caucasus, where he studied to become a priest. If in that same year a subject of the Russian empire had fallen asleep and awoken thirty years later, he or she would have been confronted by multiple shocks. By 1924 something called a telephone enabled near instantaneous communication over vast distances. Vehicles moved without horses. Humans flew in the sky. X-rays could see inside people. A new physics had dreamed up invisible electrons inside atoms, as well as the atom’s disintegration in radioactivity, and one theory stipulated that space and time were interrelated and curved. Women, some of whom were scientists, flaunted newfangled haircuts and clothes, called fashions. Novels read like streams of dreamlike consciousness, and many celebrated paintings depicted only shapes and colors.1 As a result of what was called the Great War (1914–18), the almighty German kaiser had been deposed and Russia’s two big neighboring nemeses, the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian empires, had disappeared. Russia itself was mostly intact, but it was ruled by a person of notably humble origins who also hailed from the imperial borderlands.2 To our imaginary thirty-year Rip Van Winkle in 1924, this circumstance—a plebeian and a Georgian having assumed the mantle of the tsars—could well have been the greatest shock of all.

Stalin’s ascension to the top from an imperial periphery was uncommon but not unique. Napoleone di Buonaparte had been born the second of eight children in 1769 on Corsica, a Mediterranean island annexed only the year before by France; that annexation (from the Republic of Genoa) allowed this young man of modest privilege to attend French military schools. Napoleon (in the French spelling) never lost his Corsican accent, yet he rose to become not only a French general but, by age thirty-five, hereditary emperor of France. The plebeian Adolf Hitler was born entirely outside the country he would dominate: he hailed from the Habsburg borderlands, which had been left out of the 1871 German unification. In 1913, at age twenty-four, he relocated from Austria-Hungary to Munich, just in time, it turned out, to enlist in the imperial German army for the Great War. In 1923, Hitler was convicted of high treason for what came to be known as the Munich Beer Hall Putsch, but a German nationalist judge, ignoring the applicable law, refrained from deporting the non-German citizen. Two years later, Hitler surrendered his Austrian citizenship and became stateless. Only in 1932 did he acquire German citizenship, when he was naturalized on a pretext (nominally, appointed as a “land surveyor” in Braunschweig, a Nazi party electoral stronghold). The next year Hitler was named chancellor of Germany, on his way to becoming dictator. By the standards of a Hitler or a Napoleon, Stalin grew up as an unambiguous subject of his empire, Russia, which had annexed most of Georgia fully seventy-seven years before his birth. Still, his leap from the lowly periphery was improbable.

Stalin’s dictatorial regime presents daunting challenges of explanation. His power of life and death over every single person across eleven time zones—more than 200 million people at prewar peak—far exceeded anything wielded by tsarist Russia’s greatest autocrats. Such power cannot be discovered in the biography of the young Soso Jughashvili. Stalin’s dictatorship, as we shall see, was a product of immense structural forces: the evolution of Russia’s autocratic political system; the Russian empire’s conquest of the Caucasus; the tsarist regime’s recourse to a secret police and entanglement in terrorism; the European castle-in-the-air project of socialism; the underground conspiratorial nature of Bolshevism (a mirror image of repressive tsarism); the failure of the Russian extreme right to coalesce into a fascism despite all the ingredients; global great-power rivalries, and a shattering world war. Without all of this, Stalin could never have gotten anywhere near power. Added to these large-scale structural factors were contingencies such as the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II during wartime, the conniving miscalculations of Alexander Kerensky (the last head of the Pro

visional Government that replaced the tsar in 1917), the actions and especially inactions of Bolshevism’s many competitors on the left, Lenin’s many strokes and his early death in January 1924, and the vanity and ineptitude of Stalin’s Bolshevik rivals.

Consider further that the young Jughashvili could have died from smallpox, as did so many of his neighbors, or been carried off by the other fatal diseases that were endemic in the slums of Batum and Baku, where he agitated for socialist revolution. Competent police work could have had him sentenced to forced labor (katorga) in a silver mine, where many a revolutionary met an early death. Jughashvili could have been hanged by the authorities in 1906–7 as part of the extrajudicial executions in the crackdown following the 1905 revolution (more than 1,100 were hanged in 1905–6).3 Alternatively, Jughashvili could have been murdered by the innumerable comrades he cuckolded. If Stalin had died in childhood or youth, that would not have stopped a world war, revolution, chaos, and likely some form of authoritarianism redux in post-Romanov Russia. And yet the determination of this young man of humble origins to make something of himself, his cunning, his honing of organizational talents would help transform the entire structural landscape of the early Bolshevik revolution from 1917. Stalin brutally, artfully, indefatigably built a personal dictatorship within the Bolshevik dictatorship. Then he launched and saw through a bloody socialist remaking of the entire former empire, presided over a victory in the greatest war in human history, and took the Soviet Union to the epicenter of global affairs. More than for any other historical figure, even Gandhi or Churchill, a biography of Stalin, as we shall see, eventually comes to approximate a history of the world.

Stalin, Volume 1

Stalin, Volume 1